Microsoft debuted what it thinks is a MacBook Air killer, but just like every other time it tried to kill Apple in the market this century, it’s going to fail, badly. Here’s why.

According to proponents of this myth, Microsoft is out to kill Apple’s Macs with a “new” PC it will design and build on its own. Once it arrives, they expect Microsoft to clean up not only the PC market, but also the market for Edge AI software sales, leaving Apple on the sidelines.

Why the Myth was Woven

This myth, like the iPhone iPod myth, is based on a fundamentalist faith that insists that Microsoft is invincible and Apple is inconsequential. All other alternatives are just too difficult for lazy tech analysts to fathom.

Consequently, tech analysts are very excited about any prospects for returning things back to the mid 90’s, where Microsoft could do nothing wrong, and Apple could do, well, nothing at all.

Tech analysts have warned consumers about the eminent death of Apple’s M3 Mac at the hands of devices built by Microsoft’s Copilot PC partners, and spelled out the clear facts behind their logic:

- Copilot PCs offer users a choice of devices, all built upon Microsoft’s reference designs

- Copilot PCs can offer users unlimited access to Microsoft’s software development tools for a monthly fee

- Copilot PCs can buy AI apps from Microsoft aligned software stores.

The M3 Mac can’t do any of those things. It doesn’t even natively support features like Microsoft’s Copilot chat bot, which Copilot PCs do.

That leaves an appearance of clear logic behind the prophecies of Mac doom. Apple may have reigned supreme for years, but Microsoft and their huge arsenal of partners, along with their powerful desktop PC operating system monopoly, will surely unseat Apple sometime real soon now.

Unraveled with Extreme Prejudice

The idea of a Microsoft iPod seems to make a lot of sense. Microsoft does have a history of entering markets late, but then successfully taking over and cleaning up:

- Microsoft’s Windows 95 arrived ten years late, but then took over the graphic desktop OS consumer market

- Microsoft’s Windows NT decimated the entrenched UNIX workstation market and destroyed OS/2

- Microsoft’s Office apps killed several entrenched products, including Lotus 123 and WordPerfect

- Microsoft’s Internet Explorer browser dethroned Netscape.

This all happened before

If you’ve read this far and things seem sort of strangely familiar, it’s because I originally wrote the above text for an article back in 2006. I just updated it by changing the references from “Microsoft’s iPod killer” to today’s’ supposed “Mac killer” in the form of the “new” Microsoft Copilot PC.

The original article addressed pundits’ historical hopes for an “iPod Killer” nearly ten years ago, and why all the analysts and bloggers of the day were wrong about how Microsoft would just walk in and kill Apple’s iPod.

This might remind you of the Zune, the Microsoft-designed iPod competitor that never caught on and was eventually abandoned because iPods ended up being the music player the public really wanted to buy. Nobody bought the Zune outside of a scant few trying to be “different” by ironically buying a product from Microsoft. Most Zune buyers were Microsoft employees, apparently.

But no, the article was written in mid 2006, before Zune arrived. The Zune didn’t appear until the end of 2007, which was even worse for Redmond because by that time Apple had already introduced and started shipped the next big thing, its first iPhone, in a case of spectacularly bad timing for a late coming, wannabe-iPod from Microsoft.

Back in mid 2006, the “iPod Killer” Microsoft was promoting was its Windows Media Player brand of MP3-player built by the same companies building Windows PCs. WMP was a reference design of how to beat Apple by doing something very similar looking, but in a way that profited Microsoft.

We just invented what Apple’s been doing for years now

That makes Microsoft’s old, ill-fated strategy for disrupting Apple in music players back in 2006 virtually identical to its current day strategy for ridiculing Apple and the Mac while pushing the very same product concept in a form where it is delivered instead by the companies who didn’t already think to specialize in delivering local AI rendering on the PC on their own.

But today, Microsoft is belatedly bringing the idea of locally performed machine learning to generic PC makers and then taxing the PC industry Windows-style to profit from its me-too efforts.

Rather than blazing a new trail with the “Copilot PC,” Microsoft is just rebranding its largely unused Bing Chat— while also trying to take credit for Apple’s existing efforts to reinvent the personal computer from being a commodity Intel PC into being a new high performance, highly efficient new class of ARM-powered devices equipped with an Neural Engine: specialized machine learning AI acceleration.

If you’re too young to remember the iPod wars or the other mostly forgotten history of early 2000s personal computing, you might instead call to mind the virtually identical history of Microsoft’s bold ideas for competing with iPhone. Ir tried this first with Windows Mobile leveraging its Windows PC monopoly to deliver a mobile PC monopoly, but without success.

It then had its own disastrous fiasco of the 2010 Microsoft KIN phone, which was like a less-successful version of the Zune.

Just like the Zune, Microsoft’s KIN fatefully appeared, belatedly, just as Apple was expanding beyond the iPhone status-quo that Microsoft could see to an entirely new product category: iPad in 2010.

If that’s not history ringing the same bell twice, consider also that Microsoft’s grand plans for competing with a rumored Apple tablet right before iPad arrived in 2010 was the very same thing. It was working on the Windows Slate PC leveraging its Windows PC monopoly to deliver a tablet PC monopoly, but without success.

Additionally, after iPad achieved glorious success in stark contrast to the flop of Slate PC, Microsoft again belatedly peddled out its own version of Apple’s work, the Surface/RT PC. This was again a first attempt to copy Apple in escaping the stifling legacy of Intel PCs when it jumped to using the iPhone’s novel A4 application processor as the basis for general purpose mobile tablet computing.

Something similar also occurred when Microsoft belatedly tried to copy Apple Watch with its own ill-fated Band, and when it tried to copy Siri with its own poorly received take on Voice First with the Cortana voice assistant it tried to use to generate some excitement for Windows PCs. Remember Cortana, or have you already forgotten about it as fast as Microsoft did?

Cortana didn’t last long. Microsoft is cutting support fully in June.

Today, Microsoft is doing the exact same lazy thing to again try to garner some excitement about legacy Windows PCs, this time by tacking an AI chat bot. And specifically, the Bing Chat bot nobody cared about before Microsoft rebranded it as Copilot.

Counting the Surface tablet and Windows RT, and the time Microsoft pretended to “design” its own advanced SoC just like Apple by putting RAM on a Snapdragon, this must be Microsoft’s third major attempt to ditch Intel and deliver something that could compete with Apple’s iPad, or M-powered Macs, or even both.

Can Microsoft push Apple off the Edge of AI?

The “Edge” is a term that applies to performing cost-intensive AI processing right on your local device, rather than sending AI queries to a Cloud service where the work is done on centralized warehouses of computing power and the results are sent back to the client. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft’s Azure are the principal front-runners for running software — and most recently, AI — on the Cloud.

However back in 2017, Apple introduced its Neural Engine as a specialized segment of its then-new A11 Bionic mobile processor. The Neural Engine was Apple’s marketing name for the generic concept of a specialized Neural Processing Unit. An NPU is silicon logic optimized to process machine learning algorithms the way that a GPU is specialized for offloading and computing graphics faster than the general CPU can by itself.

Also back in 2017, performing rapid machine learning calculations right on its own A11 chip allowed Apple’s new iPhone X to perform the complex facial recognition of Face ID as well as delivering the more whimsical new feature of face-based Animoji in Messages. Rather than being enthralled with iPhone X, pundits of the day ridiculed its $999 price tag and tried to make a story out of an onstage demo error that made it appear that Face ID wasn’t yet working.

They were wrong on both accounts, but more importantly, the broad spectrum of analysts and pundits who all act like they have a strong grasp on the future and what will work and what won’t, were shown to be tiny thinkers who all just repeated the low signal-to-noise clucking of the other birds in the same coup in their daily work of dutifully laying eggs for Microsoft.

Leaps and bounds of Apple’s Neural Engine

Since its debut in 2017, Apple has not only dramatically improved the performance and efficiency of its Neural Engine in silicon, but also released a series of new functions. This includes, for example, recognizing elements in text, images, photos, and other context in a new software framework called Core ML.

This all allowed third party developers to also make use of the increasingly powerful and power efficient Neural Engine in Apple’s iPhone and iPad chips.

Apple’s first Neural Engine used two cores on a 10nm silicon process to deliver 600 billion operations per second. It’s next A12 Neural Engine ran up to nine times faster while consuming one-tenth of the power, thanks to its 8 cores and a tighter 7nm process that brought performance to 5 trillion OPS.

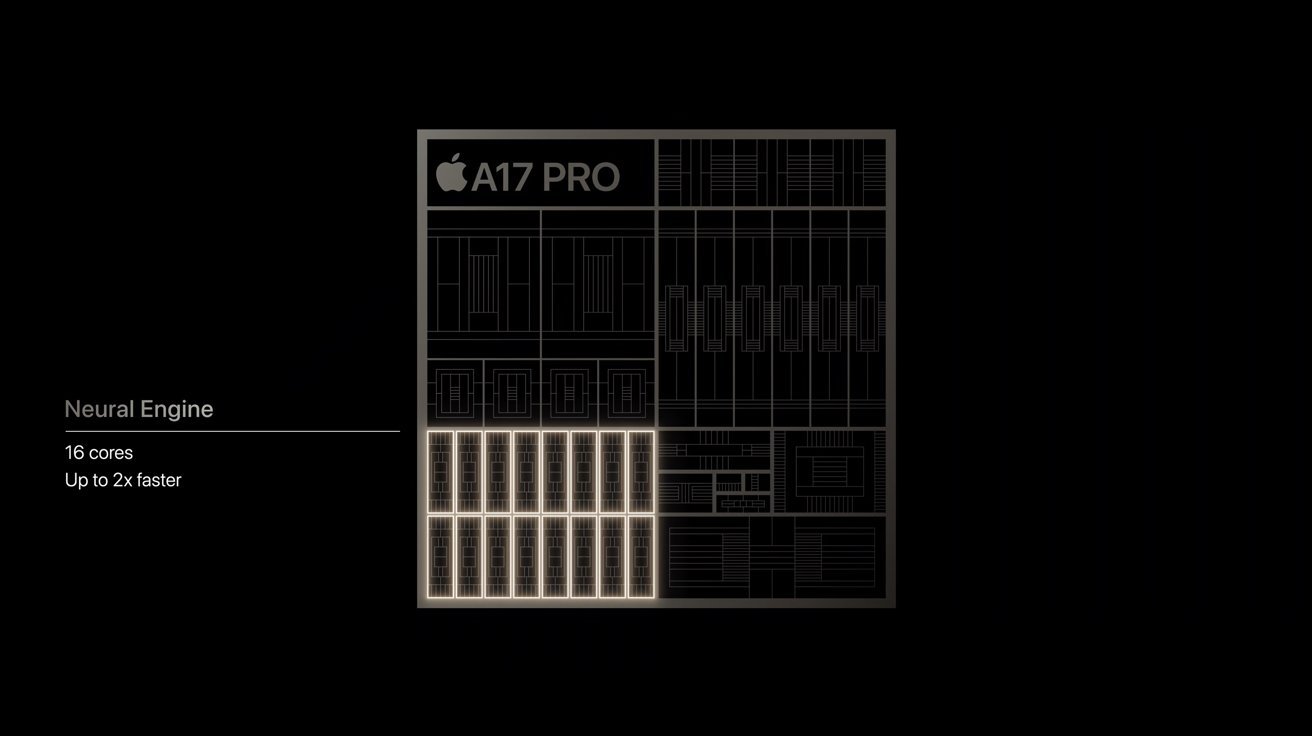

The following year, Apple’s A13 delivered an 8-core Neural Engine in 2019 delivering 20% faster performance using 15% less power. In 2020, Apple’s 5nm A14 Neural Engine delivered 16 cores that could achieve 11 trillion OPS in the service of accelerating machine learning operations.

That same year, Apple brought its in-house Apple Silicon processor technology to the Macintosh, delivering not just power efficient general performance but also that very same Neural Engine driving the identical Core ML functionality right on the device as iPads and iPhones could. That was, astoundingly, four years ago.

The performance and efficiency of Apple’s Neural Engine has been growing in pace with silicon advancements ever since. The 2021 A15 Neural Engine brought operations per second to 15.8 trillion. In 2022, M2 Macs gained a similar 40% performance jump over the first generation of Apple Silicon Macs.

Leaps in new silicon process technology helped Apple’s 2022 new 4 nm A16 Neural Engine to deliver 17 trillion operations per second at higher efficiency, while the next year’s A17 Pro leveraged a new 3nm process to handle 35 trillion operations per second in its Neural Engine. This year, Apple’s latest M4 just delivered a second generation 3nm process that introduced an even faster Neural Engine on the Mac, achieving up to 38 trillion operations per second.

Instead of any exciting clucking from the hen houses of analysts and bloggers, we heard mostly crickets.

Chickens gonna cluck when Microsoft needs an egg

Yet when Microsoft rolled out its Copilot PC concept, the pundit chickens suddenly got clucking about the potential for having AI-specific acceleration built right into the local device for security, privacy, performance and reliability.

It was as if Apple hadn’t actually been publicly deploying the largest installed base of highly performant, efficient silicon capable of handling a variety of machine learning applications since it first introduced the idea back in 2017 — on a device everyone in blogdom was saying would never catch on nor sell in remarkable quantities.

Nobody pushed the facile narrative of “the unaffordable iPhone X” harder than the Bloomberg, who insisted Apple was essentially going out of business for daring to build futuristic technology and marketing it so successfully that everyone would be desperate to spring for it no matter the cost.

In that fantasy world of pretend journalism, it was as if Apple had never done this before.

Will an AI chatbot without a Cloud rescue legacy Windows PCs?

What’s different this time around? Is there some desperate need to run an AI chatbot on a Windows PC, locally? Is there, really? Does anyone want that to occur outside of Microsoft?

What purpose does it serve apart from attempting to juice stagnant sales of commodity Windows PCs by inventing a reason to buy a new PC?

Also, did anyone ask for Recall, the parallel AI “feature” Microsoft dreamed up? The revulsion at the idea across the board suggests there will be as much demand for Copilot as there was for Cortana, the previous big marketing feature that was supposed to drive excitement in and around the inherently boring commodity market of Windows PCs.

Yet if every subsequent PC is deemed a Copilot PC, Microsoft can pretend that its rebranding of Bing Chat is a sudden sensation.

If you’re really old, you might remember how much effort Microsoft put into Bob, its original stab at making the PC seem exciting and futuristic with a chat bot that delivered seldom-useful assistant features. Has the entire company just never had an original thought?

Steve Jobs once referred to Microsoft as the “photocopier in Redmond,” an apt description of its myopic sense of creativity and invention.

On the eve of WWDC 2024, when Apple is expected to deliver details on its own advancements in machine learning and other AI features on its Neural Engine Macs and mobile devices, it seems like desperate timing for Microsoft to pull out another PlaysForSure, another Zune, another Windows Mobile, another KIN, another Slate PC, another Surface RT, another Bob/Cortana/Copilot, and then arrogantly suggest that it is actually way ahead of Apple, and won’t you please buy a slightly altered version of our Windows PC that does today what Apple will probably never do, yet also is already doing, and actually has been doing quite successfully for more than 6 years now.

How can Microsoft do this with a straight face? Mostly by comparing its fastest Copilot (I.E. Snapdragon) PC equipped with cooling fans and no provision for battery conservation against, not Apple’s previous generation M3 chip, but only Apple’s lightest, slimmest, fan free ultra-efficient MacBook Air that uses an M3 chip. And crowing itself with success over one select benchmark as a dubious accomplishment while making no mention of the fact that Apple has been selling M-based Macs equipped with a Neural Engine for the last four years, resulting in a large installed base that can already perform Apple’s AI.

Copilot PC has an installed base of Zune.

Back in 2006, I finished my original article on Microsoft’s iPod Killer the same as I can now — “Microsoft clearly just doesn’t get it, and the market will consequently punish them severely for it.”

One thing that could be different this time around: back in 2006, for my original iPod Killer article, I had to manually edit layers of a graphic to come up with a composite illustration portraying Steve Ballmer as trying to take down a plane full of iPods. Today I could ask an AI tool like Midjourney to compose something like that for me.

Things incrementally change rapidly in the tech industry, except for Microsoft and its photocopy culture.